Our communities across the world are currently living in the midst of a global pandemic, a very unsettling and challenging period for us all. We have been, and still are, experiencing an even greater threat to our societies – a hugely serious climate crisis. With terrible irony, none of us can fail to have noticed the enormously positive impact that a significant reduction in human activity has had on our environment. Our air is purer, the views are clearer, and coastal waters are often now a beautiful turquoise rather than a polluted grey.

This is yet further compelling evidence (as if it were needed) for the importance of ensuring that our buildings address issues of sustainability, energy performance and the low carbon agenda right here, right now. All designers, including those of us at NORR who are privileged to work on public projects of great importance to our communities, must do our best to embrace the greenest, most appropriate, most environmentally effective solutions we can. So must the Governments who create the legislative context for our endeavors.

Different Governments do however adopt different, sometimes rather idiosyncratic, and occasionally downright irresponsible views on climate change, its effects and what we can all do to address it. Thankfully, here in Scotland our Government has recognized the challenges for some time and committed us to highly ambitious carbon reduction requirements, including a target of net-zero emissions of all greenhouse gases by 2045. As designers, we are aware of our duty to help our nation achieve these collective societal goals. In the public sector in general, and in the education sector in particular, these ambitions have been reflected in the creation of very onerous energy performance targets which all new schools funded by the Scottish Government will require to meet. Each new Scottish school will need to deliver 67 kWh/m2 (21.2MBtu/ft2), a commendably ambitious target for operational energy demand, designed to provide a high performing educational estate for future generations. Add to this a new revenue (rather than capital) based funding mechanism and we have a collective recipe for encouraging national success.

But at what cost?

Low energy performance is a critically important (perhaps the most important) feature in any current design, but it is not the only one. It is just one of the diverse array of factors that any good architect has to consider – context, townscape, quality of natural light, connections between inside and out, effective functioning, diversity of volume, orientation, materiality, often highly challenging budgets, inclusiveness and the health and well-being of users are all just a few of the many influencing elements that the architect has to contend with. Good design is, by its nature, holistic. And great design delivers all of this in a poetic, empathetic, site-specific, culturally resonant way. This can lead not only to increased creativity in how we deliver these requirements, but also, occasionally, to increased tension between the pursuit of a low carbon solution and the quality of the design we are trying to achieve.

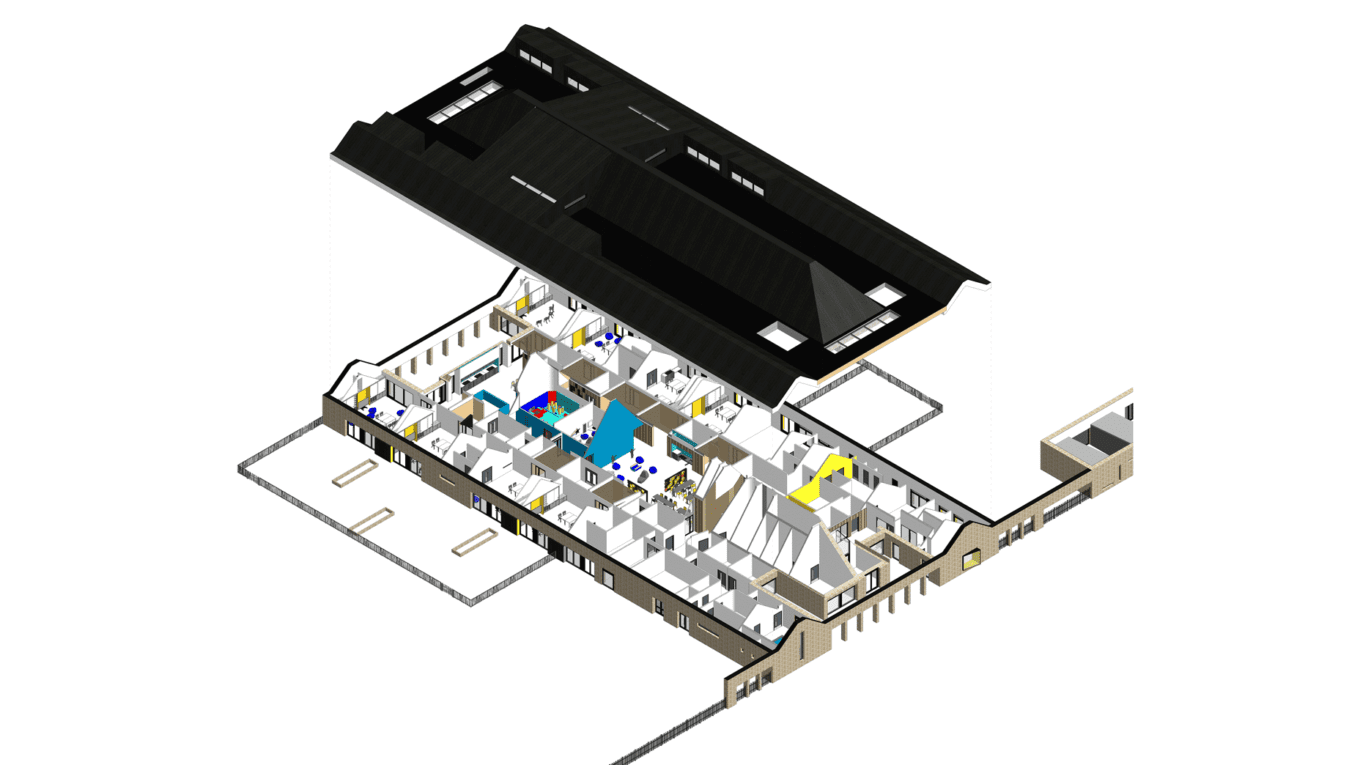

A very simple example would be the configuration of a window in a typical classroom. We are currently designing a Special Needs School for one of our excellent public sector clients, a building type that we are particularly passionate about. The emerging design has a compact form and an excellent external wall to floor area ratio, both strategic moves conducive to effective, sustainable design. Passive design principles also suggest that a wide, horizontal window would be best to control heat loss in a typical classroom situation, however, this isn’t necessarily the most appropriate arrangement for the project’s context or its users. This arrangement doesn’t necessarily deliver the best quality of space, or the best quality of natural light either. And surely strong connections between inside and out have innumerable benefits, whether practically, aesthetically or psychologically. The pragmatic ability to move between inside and out is so beneficial. Wider views through large glazed walls can simply be beautiful, whether we’re able-bodied or not. And those who find themselves partially or even fully incapacitated in a motorized wheelchair, where sensory experiences are (we imagine) essential to one’s quality of life, would surely want to have the opportunity to embrace these experiences – to take in the majesty of a winter landscape, observe the local wildlife, feel the sun on their faces or sense the light changing in their eyes; we’d wish to feel those moments of joy.

That is, ultimately, what our school buildings aim to do.

There won’t however, be much joy for our descendants without a planet to experience it on. That’s why we always work and will continue to work, both enthusiastically and creatively with other talented environmental designers and engineers, to achieve the optimum balance between often apparently conflicting factors.

After all, that is architecture. What is design other than a sublime compromise?